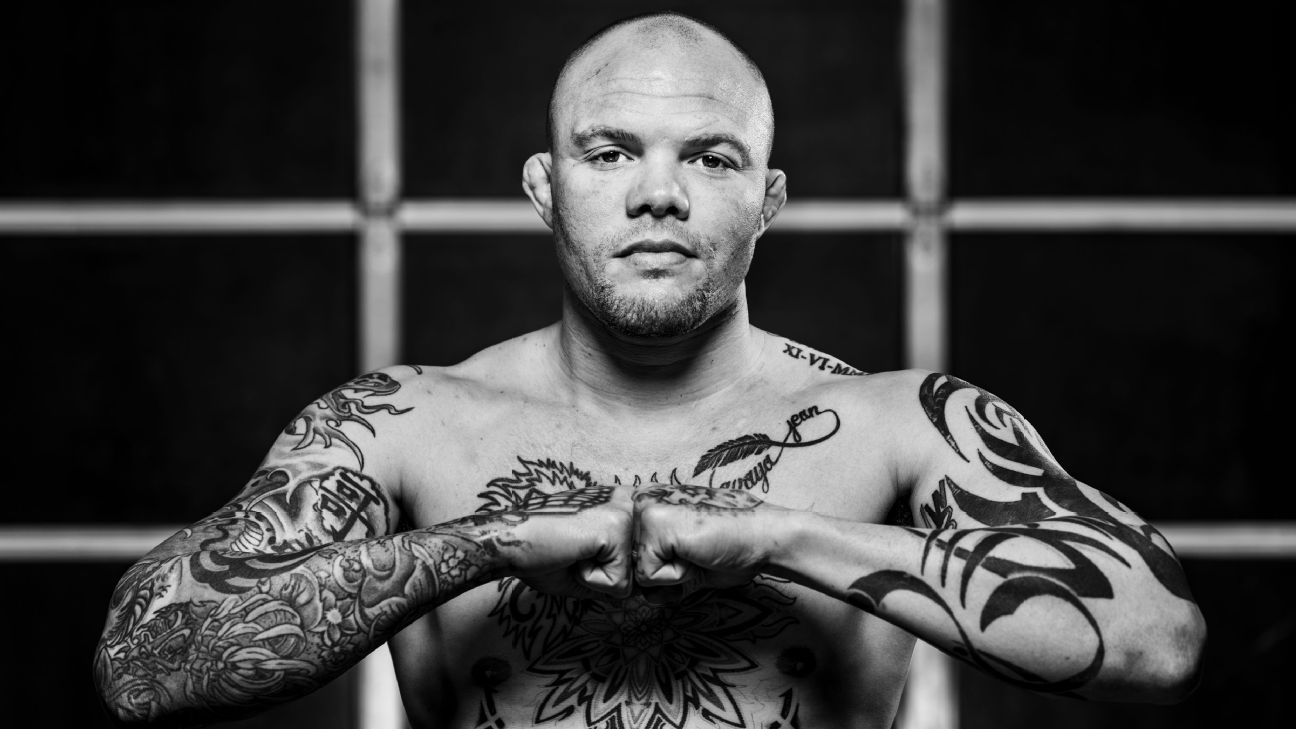

SCOTT MORTON HAS been watching Anthony Smith fight for the last 17 years, but on Dec. 9 in Las Vegas, he was certain that he never wanted to do it again.

At a UFC Fight Night that evening in the UFC Apex, Smith suffered a walk-off knockout loss to Khalil Rountree Jr. The end came in Round 3, when Rountree landed a left hook that sent Smith reeling to the canvas so awkwardly, that Rountree refrained from throwing another shot even though the referee hadn’t yet waved him off. Morton, Smith’s longtime jiu-jitsu coach, accompanied Smith to the back, sat with him as he went through medicals and then broke into tears.

There was no sense in doing this anymore, he said. And it never needed to happen again.

“I told him I didn’t want him to do it anymore,” Morton told ESPN. “I sat in the corner that night and watched half of his brain get turned off, while the other half fought to keep working. I told him that he’s reacting to getting hit differently, and the other guys aren’t reacting to our shots the way they used to. I told him he’s one of the best in the world, and there’s nothing left to prove.”

And so began one of the most dreaded conversations in combat sports. When is an athlete done?

For now, Smith (37-19) isn’t done yet. The 35-year-old will appear in his 57th professional fight at UFC 301 on Saturday in Rio de Janeiro (ESPN+ PPV, 10 p.m. E.T.), against 26-year-old Brazilian Vitor Petrino (11-0). Petrino is 4-0 in the UFC and is considered a power puncher. Seven of his 11 wins have come by knockout. A victory over an established veteran such as Smith would likely propel him into the Top 10 of the light heavyweight division.

Morton, who has coached Smith since 2007 in their hometown of Omaha, will be in the corner this weekend. Despite his feelings about the last one, he supported Smith in taking this fight. The two made each other a promise when it was offered though: from now on, everything is one step at a time. For the first time, really ever, they’re not thinking about a path to the UFC championship or even a win or loss. Just live in the moment, perform to the best of their ability and reevaluate after.

“I’ve realized that if I don’t give up on the idea of winning a title — obsessing over it — it just guarantees that it will never happen,” Smith said.

It’s a sensible change in mindset, but it doesn’t really address Morton’s concern from December. If Smith goes out and wins on Saturday, it will reaffirm what they already believe, that he’s still capable of doing this at the highest level. But if it goes sideways, there’s a good chance they’ll be right back where they were after the last one — questioning where the sense was in even being there.

Smith’s head coach, Marc Montoya, calls it the fighter “conundrum,” and he’s watched it play out over and over as a coach of the last 16 years. Smith is still ranked and still younger than three of the past five men to have won a light heavyweight championship for the first time — including the current champ, Alex Pereira. He’s paid well. Why would he stop?

He has also been on the wrong end of some memorably vicious losses in recent years. He’s a father of four, financially set and already considered one of the best light heavyweights of his era. So, why continue?

Fighters answer that last question in so many ways. They continue to fight because they still feel good in the gym. They say they want to set an example for their kids, that you don’t quit when things get hard. They enjoy proving their doubters wrong, and tell themselves that if one or two things just fall into place, they’ll be able to walk away from the sport on top, on their own terms.

But internally, there’s another reason they keep going — and Smith is willing to admit it, on the record, at this point in his career. It’s that the scariest part about fighting isn’t getting hurt or losing in front of your loved ones anymore. The scariest part is the idea of never fighting again.

“I’m terrified of retiring,” Smith said. “My entire adult life, all I’ve done is chase a 10-pound piece of gold. Who am I once that stops?”

SMITH LIVES IN OMAHA, but his camps take place at Factory X in Englewood, Colorado. During camp, he stays in Colorado throughout the week, and flies home to be with his family every weekend.

Montoya oversees the gym’s stable of fighters day-to-day, camp-to-camp — and eventually, they all ask the question: “When do you think I’m done?” In his experience, an athlete is done when he or she can no longer mentally and physically put in the work the sport requires. Outsiders focus on wins and losses, but for Montoya, it’s more about the work. And usually, the body actually outlasts the mind.

“It’s actually never the result in the cage for me,” Montoya said. “It’s losing that in-love feeling of training. Everyone wants to fight. Fighting is fun. The training is the hard part. And when they fall out of love with the training — the being away from your family, the grind — that’s when you start feeling the signs of, ‘OK, we might be coming to the end here.'”

Smith will flat-out admit that he doesn’t love fight camps anymore. He and his wife, Mikhala, have four daughters. Their 12-year-old played in a national qualifier volleyball game last month in Kansas City, and Smith couldn’t attend or even watch live because of fight obligations. He missed most of their 9-year-old’s basketball games last season. He coaches their 6-year-old in wrestling, and she made it all the way to state — but then didn’t attend, because her dad wasn’t available to go. Their 2-year-old has a speech delay, and Smith has missed several milestones of her working through it.

He wonders how his daughters will feel about that once they’ve grown. What those conversations will be like.

“I think about it all the time,” Smith said. “I am still in love with training. When I’m in the gym, I’m exactly where I want to be. It’s the before-and-after training that I am no longer in love with. That’s the disconnect. When I’m sitting in Denver alone, watching bad Netflix, I think about what fighting is costing me. And is the return on my investment worth it? I still haven’t figured that out.”

Smith is not alone in his plight. Not in the sport, not even at UFC 301. Jose Aldo, one of the greatest fighters of all time, is coming out of “retirement” at age 37. Aldo (31-8) hasn’t fought in MMA since 2022, although he has been boxing professionally during that time. The former champion will be inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame later this year, and yet he’s still competing this weekend. Karolina Kowalkiewicz, 38, has won four in a row after coming within one loss of retiring during a five-fight skid in 2021. Both have grappled with similar questions to the ones Smith is having now.

“I’ve talked a lot about the end with [coach André Pedeirneras], my family, my wife,” Aldo told ESPN. “Ultimately, my goal is always to become a champion again. I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t think I could make my way back to the title. Financially, I don’t need to it and I wouldn’t trade my health for financial reasons.”

Although retirement — and staying retired — looks different for each athlete, it’s universally cruel. The way Montoya puts it, most kids don’t find fighting, fighting finds them. And then fighting chooses when it’s time to break up.

“One of the reasons these guys become good humans is they find an outlet in fighting that if they didn’t have, they would be in massive trouble,” Montoya said. “Prison, death, drugs, all of the above. It’s scary to them to take away the one thing that was able to put them on the right track. Their two most powerful [ways of] dealing with taking that away are time and patience. But you’re talking about a kid who will fight you in the parking lot if you ask them to because that’s all they’ve trained to do. Now, you want to tell them to take time and be patient? They’re like, ‘F— you, I don’t even understand what that means.'”

Smith said there was a time in his life when he didn’t think he’d be alive at 35, because he was “living so fast.” So, the idea of now adjusting his life due to getting older is hard to wrap his mind around. He’s been conditioning himself to fight for so long, he said he doesn’t feel capable anymore of not fighting.

In July 2022, Smith suffered a broken leg during the first round of a fight against Magomed Ankalaev. Despite the injury, he answered the bell for the second round and fought on for three more minutes before losing by TKO. Looking back, he knows there was no sense in that, but also feels it wasn’t even a conscious decision that he made.

“Most people would have sat on that stool with a broken leg and said, ‘I can’t fight,'” Smith said. “I just can’t f—ing say that. I knew it wasn’t going to end well. I knew Ankalaev was too big and too good to beat on one leg, but I couldn’t say it. Think about this, Petrino is 11-0. Through my first 11 fights, my record was 5-6. I shouldn’t be here. I was never good enough to be here.

“My career wouldn’t even exist if I had been smart enough to know when enough was enough. But I kept banging my head against the wall until it eventually went down.”

A lot of walls have fallen down for Smith in the past 17 years. He really has built an entire life for himself by simply refusing to go away. It’s one of the trademarks of his career. But what happens when the walls stop falling?

“I have always said that I want to be the guy who is done with fighting before fighting is done with me,” Smith said. “But I also know that the mindset that got me here, is also what’s going to be the death of me.”

UFC 301 IN BRAZIL will not be the final career fight for ‘Lionheart’.

As of right now, whenever Smith accepts a fight offer from the UFC, he’s essentially accepting two. That’s because he intends to take a “retirement fight” whenever the day comes that he does decide to hang up his gloves. He said it’s because he wants to let his friends and family know that it’s his “last ride,” so they can be in the building for it if they want.

What UFC 301 will be, however, is a test. Smith has his new mindset going in, of not placing so much pressure on himself to constantly move toward a title. He has a game plan for Petrino, and he’s promised to stick to it more than perhaps he has previously. Again, he’s had so much success through sheer stubbornness, it’s a habit that dies hard. But Morton has pleaded with him to fight smarter — older, you might say — than before.

“I want him to not be so reckless,” Morton said. “There’s always been a measure of you didn’t know what was going to happen when Anthony fought, because he had that mentality of going after you and presenting a problem. I want him to be a little less loose and protect himself now.

“Put it this way, the last time we went to Brazil, he fought Thiago Santos (in 2018) and it was an amazing fight. They split each other open, knocked each other around and won Fight of the Night. That’s not the fight I want Anthony to be in going down there this time.”

If he wins but doesn’t look like himself, there will be a conversation. If he loses but performs well, there will be a different conversation. If he loses badly, there might be a difficult conversation.

How that process will go is anyone’s guess, and it’s interesting to ask each person who might be involved about it, separately. You get different answers.

Mikhala, who has been with Smith since the very beginning of his career, believes that when the time comes, her husband will see reason. She used to worry about how he’d cope in retirement, but she doesn’t anymore. Smith works as an analyst for ESPN and co-hosts a successful podcast, “Believe You Me,” with retired champion Michael Bisping. He’ll be able to stay around the sport and have purpose when fighting is done.

“He’s really good at convincing himself and other people, but he can’t convince me,” Mikhala laughs. “I think Marc, Scott, myself — there might be a time when we have to say enough is enough, and I’m prepared for that day if we ever get to that position. But he’s always told me that when I say it, that’ll be it.”

“I have always said that I want to be the guy who is done with fighting before fighting is done with me. But I also know that the mindset that got me here, is also what’s going to be the death of me.”

Anthony Smith

Montoya is not as optimistic. He believes there will be a conversation. His long history with fighters tells him there will be. And he has an idea of how it will go.

“There will be a conversation, mark my words,” Montoya said. “Ultimately, it will fall on my shoulders, and I always dread that day because it’s very rare you get a, ‘You’re right coach, I love ya.’ Typically it ends badly.

“And it sucks because we’ve spent so much time together in life. Fighting gives us the ability to do life together. And a lot of times when you have to have that conversation, they tell you, ‘Oh, you don’t believe in me anymore.’ It’s not true. It has everything to do with sustaining their future. I give my all to these guys and when I lose them, it’s a void. It’s a void in my life and it’s a void on their side, and it f—ing sucks.”

Smith agrees with his wife. When she says he’s done, he says he will be. Although he can’t help but add, “I don’t think they would ever stop supporting me. That’s what they say, but they’d still show up every time if I went on.”

All of it is speculation, and right now, it doesn’t matter. Because right now, Smith isn’t done. He will fight on Saturday — whether there’s sense in it or not.