Sky News looks at the assisted dying debate from unique perspectives: Mick, who watched two friends die at Dignitas; Sue, who wishes her husband could have died faster; Michael, who has MND and opposes assisted dying; and Brendan, whose close friend Dave Courtney, took his own life.

Ann was a talented canoeist. She enjoyed climbing and camping with her equally active husband, Bob, who was once the manager of a mountain rescue team in South Snowdonia.

The pair had been “fit as fleas”, their close friend Mick Murray tells Sky News, but that rapidly changed when they were both diagnosed with terminal illnesses in their 60s.

Ann was first.

In 2013, she was told she had progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a rare neurological condition that starts with symptoms such as muscle stiffness, extreme fatigue, and blurred vision, similar to Parkinson’s disease.

In its most advanced stages, sufferers begin to experience problems with bowel and bladder functions, and increasing difficulties controlling the muscles of their mouth, throat and tongue.

Ann was told she could die after getting pneumonia, or that her tongue might suffocate her because she could no longer control it.

There was a good chance she would end up needing a feeding tube to prevent choking and chest infections.

They were advised the prognosis for PSP is typically around seven years.

But just a few months after her diagnosis, Ann, 67 at the time, was unable to stand, feed or dress herself, or go to the toilet unaccompanied.

Mick watched as his friends left their home in North Wales for sheltered accommodation in Cheshire, where Ann could receive help for her “rapidly deteriorating” condition, the life they had built together completely uprooted.

When it became clear no medicine could improve her condition or alleviate her symptoms, and because assisted dying is illegal in the UK, Ann decided to end her life at Dignitas.

“Bob was completely bereft,” Mick recalls.

“He couldn’t believe the person he’d been with for so long could just almost collapse. There was also this terrible feeling of powerlessness. You don’t know what to do, just watching someone disintegrate in front of you.”

The Dignitas clinic is a two-storey house in the suburb of Pfaffikon, near Zurich, in Switzerland, bought in 2009.

There is a garden and stream there, and on their final day, the patient is free to “wander around and sit out in the sun” before going back inside, into their bed.

Ann and Bob travelled there in February 2014, accompanied by Mick and a few of the couple’s other close friends.

For two consecutive days, she faced questions about her reasoning. Was she of sound mind? Was she being pressured? The questions continued to be asked right up until her final moments.

“She accepted the fact she was never going to get better,” Mick says. “She fought it to the extent that she could. She was still alive in spirit right until the end.”

Dignitas staff, he says, offer to link arms and sing a song requested by patients.

Ann chose The Lady In Red by Chris de Burgh.

She was then given a lethal drug dissolved in regular drinking water.

The patient has to take the drugs themselves to categorise it as an assisted death, rather than euthanasia.

Ann had to have a cannula and press a button to release the drug herself, as she wasn’t able to drink it. Encouraged by the staff, her family and friends kept talking to her after she lost consciousness.

The experience was harrowing, says Mick, despite the staff there being kind and sympathetic.

“I rationalised it after the event and thinking about it, it was an honour to help my friend to die,” he says. “But at the time, it’s pretty awful.”

Mick was back at Dignitas just a year later.

The lead-up to Bob’s death, much like his wife’s, was sudden.

Walking with Mick in the Peak District in January 2015, Bob stopped, short of breath. He couldn’t continue, he told his friend, despite still being in “extraordinarily” good shape.

By April he had been diagnosed with mesothelioma, a type of cancer typically affecting the lining of the lungs. The pain soon became “unspeakable, excruciating”, says Mick, and he spent most of his final months medicating it away.

“All he could do was sleep, really… he’d get into a chair, take all these drugs and basically pass out until they wore off. And then you might have an hour where it was okay and then it all started again. It was utterly debilitating.”

Bob, who was 68, made the decision to die in the same way as his wife and travelled to Dignitas in August 2015, choosing to listen to Beethoven’s Ode To Joy as he lost consciousness with Mick at his bedside.

It was another difficult experience – but Mick was glad that Bob, like, Ann, got something close to the death that he wanted.

He says they would have much preferred to die at home, surrounded by all their loved ones.

‘Please make it stop. I’m ready to go’

Sue Biggerstaff was married to Simon for 17 years before his “agonising” death in May 2022.

The pair lived in Ballabeg, a village in the Isle of Man, where assisted dying may soon be legalised.

In April 2021, Simon “started having the odd fall when he was out with his dog, Ella, and he blamed it on the long grass in the field”, Sue says. But then he collapsed at work and quickly deteriorated; by the time he got to his first doctor’s appointment, he needed a walking frame.

On 1 July, he was given a formal diagnosis of motor neurone disease (MND), which affects the brain and nerves, and told it was an “extremely aggressive” form. It wasn’t long before the 65-year-old was paralysed from the neck down.

“You’ve got to imagine what it’s like,” Sue says. “Even if you have an itch, you can’t scratch it. You’ve got to ask somebody.”

Simon hated the fact she had to do everything for him, she says. He did not want her to be his carer. The pair made every effort to maintain some quality of life, buying a wheelchair-accessible van so they could go out together.

“But eventually it was too painful for him to even sit up” and he was permanently bedridden, Sue says.

Simon then started getting terrible pain in his back due to a chronic bed sore, and developed severe stomach complications.

Sue eventually asked a nurse: “Why is this so bad? Why can’t you get rid of it?”

Her voice cracks as she recalls the nurse saying her husband’s skin was effectively decomposing.

Some of Simon’s teeth would simply go missing, Sue says, because his gums were receding. She was told he’d have swallowed them without realising.

He was taking a “cocktail” of drugs, including morphine, but the pain became too strong and the drugs started to lead to extreme hallucinations. Simon, who had a fear of horses, kept seeing the animals in their house.

“I was permanently taking horses out of the lounge,” Sue says. “It sounds ridiculous, but they have these horrible hallucinations… it’s very real and there’s no convincing [them].”

Simon started pleading with her. “Please make it stop. I’m ready to go.”

A nurse told Sue that giving him any more drugs would put him in a coma.

Sue told them: “Well, put him in a bloody coma then.”

Simon, who could barely communicate in his last few weeks, had told his wife he hoped to live for one more Isle of Man TT, the annual motorcycle racing event. Then, Sue says, he wanted her to starve him to death.

Instead, he died of the effects of MND without intervention on 29 May 2022, two days before the TT.

Having seen what her husband went through, Sue is “terrified” of getting a terminal diagnosis. She “desperately” wants assisted dying to be legalised in the UK. They never considered Dignitas for Simon due to the costs and how quickly the trip became unfeasible for him physically, but he would have wanted it in his final “unbearable” weeks, she says.

Those against it “usually haven’t seen people suffer”, she adds. “I don’t want to see anybody suffer like Simon did.”

‘My life is limited by illness – but I oppose assisted dying’

While two in three Britons (65%) believe assisted dying should be legal, according to an Ipsos poll taken in 2023, the same poll shows 17% of UK adults are against a law change, while 18% are undecided or prefer not to say.

Despite losing all independence since he was diagnosed with a form of MND in 2002, Michael Wenham, 74, is among the 17%.

Michael, who lives in Oxfordshire, needs help to get out of bed, get dressed and go to the toilet. He has to have food prepared for him and cannot stand, sit or shower without assistance. He can spend time on his laptop, read, write, and listen to the radio or watch TV, before being helped back into bed by Jane, his wife of nearly 50 years.

It’s all very mundane, Michael tells Sky News via email. This is the best way to communicate, he says, as his speech is “barely intelligible” now. His life is a far cry from his earlier years, when he worked in publishing, as a hospital porter, and taught English for 10 years before becoming a vicar.

His diagnosis of primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) – a slow-developing form of MND – would most likely make him eligible for an assisted death at Dignitas. And yet, he says he is more grateful than ever to be alive.

“I’m more grateful than I used to be although – or possibly because – my life is much more limited,” he says. “I get to appreciate small kindnesses, and physical help. I wake up grateful to see another day – what a gift – which I used to take for granted. Life is so full.”

It’s not just that Michael wants to keep on living – he is fervently against assisted dying.

“I believe it’s dangerous,” he says. “History and experience in other jurisdictions convince me that once you open the door to the taking of life, it never shuts; it only opens further.”

Critics like Michael point to Canada, where the criteria for medically assisted death has slowly been expanded since it was legalised for people with terminal illnesses in 2016.

In 2021, the threshold was lowered to include people with incurable, but not terminal, conditions. Later this year, people in Canada whose sole underlying condition is mental illness will also be able to choose an assisted death, should they pass a series of checks.

The current assisted dying laws in the UK

Mick not only accompanied Ann and Bob to Dignitas, he also organised the trips for them – despite knowing it was a criminal offence.

Under current legislation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, assisted dying is completely banned without exception, which means family and friends can face up to 14 years in prison if convicted. In Scotland, it is not a specific criminal offence, but assisting the death of someone can leave a person open to murder or other charges.

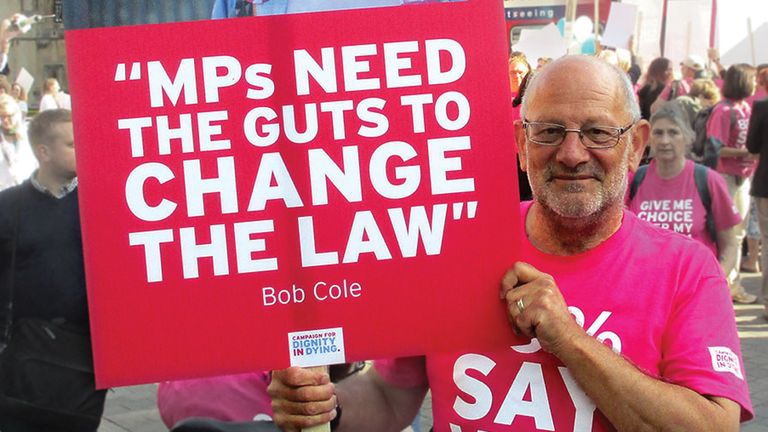

“We had no fear of protesting against what we thought was an unjust law,” Mick says. “If you’re acting out compassion, I don’t think you should be scared to stand up for yourself and just admit you did it.”

He says he doesn’t know why he was never questioned by authorities over his involvement in his friends’ deaths.

Guidance published by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in 2010 outlined not only the laws prohibiting assisted dying, but also some “public interest factors” against punishing someone who has broken the law. “Prosecution does not follow automatically whenever an offence is believed to have been committed,” it says.

There are nine factors which make prosecution less likely, including being “wholly motivated by compassion”, and the person suffering having made a clear and informed decision themselves.

Mick now campaigns for change with the pro-assisted dying group Dignity In Dying. Asked how Bob and Ann would have coped had they not been able to go to Dignitas, he says Ann would have died “badly”. Bob, he says, would have taken his own life anyway.

Dave Courtney: The gangster who couldn’t take the pain

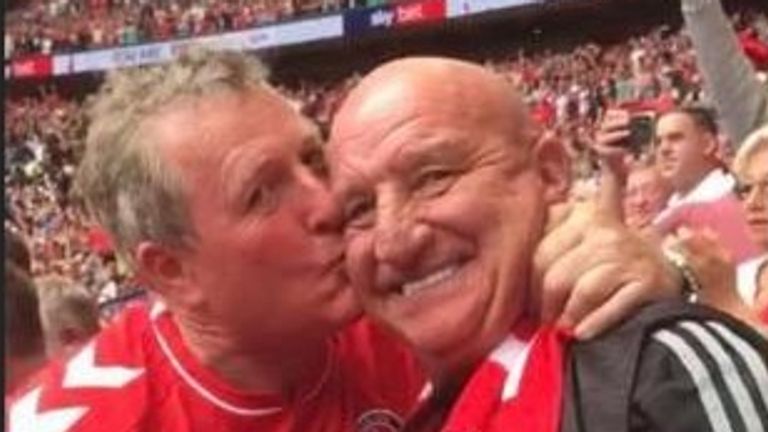

You might recognise Dave Courtney. He was a reformed gangster turned actor, who appeared in a handful of crime documentaries and low-budget gangster films. Courtney claimed to be an associate of the infamous Kray twins and said his exploits had inspired Vinnie Jones’s character in the film Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels.

“An action-packed hero,” says Brendan McGirr, his lodger and best friend of more than 30 years. “He was really, really tough and a strong character.”

In October 2023, he took his own life, aged 64, turning a gun on himself at his home in southeast London.

In the years beforehand, as he battled rheumatoid arthritis and several other serious health issues, including prostate cancer and treatment for a replaced heart valve, Brendan watched Dave change. By the end, he had become his official carer.

“The last three months, the pain was so exceptionally high,” Brendan says. “He literally sat in the chair some days with tears coming out his eyes. He was slowly deteriorating with his mobility.”

The suicide rate among people diagnosed with incurable health conditions such as low-survival rate cancers, or serious lung diseases that affect breathing, is more than double the average rate, according to ONS figures released in 2022.

A year prior to his death, Dave confided his intentions to his friend.

“He explained to me the reasons,” Brendan says. “Obviously, I didn’t want him to take that action because I loved him so much and we’d been so close. But I also didn’t want to see the amount of pain he was in with the arthritis.”

It was Brendan who found Dave’s body. He died alone, having secretly recorded video messages for his family, who were unaware of his plans.

“He didn’t talk about the need for assisted dying,” Brendan says. “But I think, had Dave had the choice, he would have been able to discuss it properly with his family and loved ones, and he would have loved everyone to have been with him and had a last meal with him, shared that moment and said goodbye properly.

“The amount of mental stress that he must’ve gone through in the last two years to plan this meticulously… he’s had to sit there on his own and record personal messages for all his family months before he passed.”

Could the tide be turning on assisted dying in the UK?

Assisted dying being legalised in at least one jurisdiction of the UK or Crown Dependencies is looking “increasingly likely” and the government must be “actively involved” in discussions about what to do if that happens, MPs have said.

The Isle of Man is on course to become the first part of the British Isles to legalise assisted dying for terminally ill people after its parliament, the House of Keys, voted by a 70% majority to pass an Assisted Dying Bill last year.

Provided the landmark bill gets through the next steps of parliamentary scrutiny, the island will become the first part of the British Isles to legalise assisted dying. A similar bill is set to be put to Scottish parliament imminently.

It would allow terminally ill adults living on the Isle of Man, who have been given six months or less to live, the option to end their own life with assistance from healthcare professionals – following a series of safeguarding checks to ensure they are mentally competent and have a “clear and settled intention to end their life”.

The new law would only apply to residents of at least a year, meaning the Isle of Man is unlikely to become the new destination for UK residents who wish to end their own lives. However, pro-assisted dying campaigners believe it could show the UK the merits of changing the law.

Campaigners against assisted dying also believe it could spell a wider change.

The bill was put forward by Dr Alex Allinson, a GP, who is also the Isle of Man government’s treasury minister.

“As a doctor, I looked after a number of people who decided they wanted to die with the support of a hospice,” Dr Allinson says. “I was in a position where several of them sort of said to me, ‘Is there anything we can do to speed this up? Is there anything you can do to help me? Because I’m suffering and I know what’s going to happen, and I’d like to be in control of it’.”

He remembers how one of his patients asked if he could help her with the process of getting the “green light” to end her life at Dignitas.

As it stands, doctors are very limited in what they can say to a patient about assisted dying, as they could be prosecuted if they are deemed to be helping them. He had to inform her the law prohibited his involvement.

“That got me thinking that we can do better,” Dr Allinson says. “And it motivated me once I got into parliament to work with other members to bring forward this legislation.”

It is stories like Dave Courtney’s that also played a big part in his campaign.

“I think people are taking matters into their own hands, but doing it completely alone without the ability to express their wishes to anyone else, including their family and their doctors,” he says. “By changing the law, even though probably very few people will want to take it up, I think there will be that ability to have a lot more honest conversations about what people are facing and what they want for themselves and their loved ones.”

Sarah Wootton, chief executive of the campaign group Dignity In Dying, says the Isle of Man’s vote was historic.

“It’s clearly an issue whose time has come,” she says. “I think that to do nothing on assisted dying is the most dangerous choice of all.

“The blanket ban on assisted dying is not working. And I think evidence of harm inflicted by it is mounting, with dying people who are suffering against their wishes forced to take matters into their own hands or abroad.”

But campaigners against assisted dying, such as Gordon Macdonald, chief executive of Care Not Killing, say it is a “slippery slope”.

Mr Macdonald believes the majority of problems people with terminal illness are facing can be solved through palliative care, which focuses solely on comfort, rather than attempts to improve a patient’s condition.

That involves psychological, social and spiritual support, according to the NHS.

“A lot of what people are looking for is somebody who has the time to sit at their bedside and talk to them and listen to them,” Mr Macdonald says. “You don’t get that in many areas of medicine, sadly, because healthcare staff are so overworked.”

But, Mr Macdonald says, if it were to be legalised in some form in the UK, it “can never be guaranteed” that the laws would remain the same once passed.

Anyone feeling emotionally distressed or suicidal can call Samaritans for help on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org in the UK. In the US, call the Samaritans branch in your area or 1 (800) 273-TALK